I

had no knowledge of the Online Parish Clerk (OPC) program when I first started

my genealogical investigation of British records. It started off innocently

enough when I went to find out more about my direct-line, paternal ancestors.

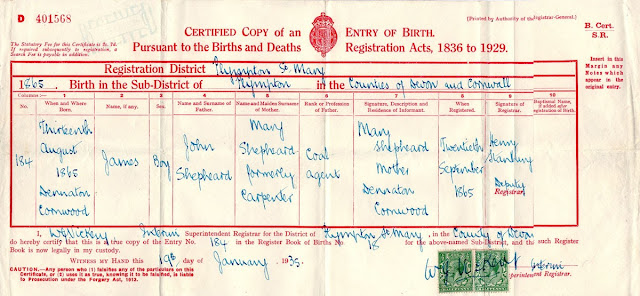

From

a few bits of information I had about my Shepheard line, including two birth

certificates inherited from my father, I knew my grandfather had been born in a

place called Torquay in Devon, England, and his father had been born in

“Dennaton, Cornwood” (wherever that was), in the “Sub-District of Plympton in

the Counties of Devon and Cornwall.” The birth certificate issued by the General

Record Office for my great-grandfather is shown below.

These

documents gave me a couple of starting points for what would become a very long

and still-not-ended journey. The reference to Cornwood, though, clued me in on

where my initial searches should be concentrated.

I

was feeling flush and adventurous when I finally got seriously involved in

genealogy. One of the first things I did was purchase all of the Cornwood

parish birth/baptism, marriage and death/burial registers which were available on

microfiche. I thought that might be the best way to discover information about

my family – go through all the registers myself and find the actual entries

pertaining to the individuals. I had my own microfiche reader/printer so it was

no problem to order and use the films at home.

At

the time, I did not realize how lucky I was going to get. It turned out that my

ancestors had lived in the Cornwood area as far back as the early 1600s so I

was about to discover hundreds of them, over eight generations, hidden in the

registers.

Interestingly,

when I found my great-grandfather’s baptism entry, there was very little

information shown. Without the birth certificate I would only have been able to

identify him at the time from census data. The Vicar appears to have lost his

notes when it came time to fill in the page in the baptism register, as can be

seen in the image below! Information for one other child baptized the same day

was also missing.

1865 September 5

– baptism entry for [James} Shepherd [sic],

in Cornwood parish baptism register #823/4, page 42; image accessed from

FindMyPast March 5, 2010, copyright Plymouth West Devon Record Office

This

is one of those curious situations that can be encountered occasionally with

old parish records. One has to work around them, using other sources, in order

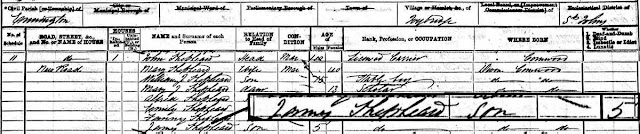

to find the full information about some individuals. James did appear on the

England census for the first time in 1871, at the age of five. His family were

then living in Ermington Parish, very near that place called Dennaton,

Cornwood. In any case, all other Shepheard children born around this time were

identified in the register leaving me to conclude that the incomplete record

had to be for James.

Portion of 1871

England Census enumerator’s sheet, page 2, folio 53, piece 2107, class RG10;

showing John

Shepheard family living in Ermington Parish, Devon;

image accessed from Ancestry November 3, 2006,

copyright The National Archives

I

did finally put together almost everything I have learned about my Shepheard

line in Devon, in a book that was distributed to many family members last

month. The early reactions from some of them are amazement of what all I have

found out and delight in seeing the history of the family laid out. It inspires

me to keep going with my other lines.

As

many people have found in their research in England, indeed, Great Britain,

parish registers are among the more important sources of information about

people. They contain the basic data on individuals – births, marriages and

deaths – over long periods of time. Not all registers are complete, or have

been preserved for every parish, and not all individuals who were born in the

various parishes were baptized, married or buried there. But the registers do

provide an excellent initial source to search for ancestors.

I

always like to get my data in an organized form; so, from the beginning, I

started transcribing all the register entries and putting the information on

spreadsheets. Shortly after receiving the fiche, I decided I could probably

help others find their ancestors, since I now had the data in hand. That’s when

I volunteered to become the OPC for Cornwood. Before long I had also purchased

the fiche for the registers of the adjoining parishes of Harford, Plympton St.

Mary and Plympton St. Maurice (I said I was feeling flush in those days) and

took on those parishes as well.

Over

time, and with the help of many other volunteers, we have transcribed almost all

of the BMD registers from my four parishes – now over 70,000 individual entries

from over 7,400 register pages. We have also done most of the censuses in the

area, another 31,000 entries from over 2,300 pages. From that work, I have a

searchable database that speeds up answering questions from other researchers.

Having the information on a spreadsheet also allows me to sort the data and

recombine it to show individual family summaries, over many generations in some

cases.

I

have had hundreds of queries, from people all over the world, looking for

information about their families who lived in my parishes or somewhere in Southwest

Devon. Most I have been able to help by providing BMD, census and other data that

filled in missing pieces of their family history and even broke down a few

brick walls. It is always gratifying to be able to assist people in discovering

their ancestors and give them more avenues in which to search.

Some

of the queries have resulted in some very interesting and surprising stories, many

of which I will discuss in later posts.